You read that title right. It means screenplay writing rules for writing a book.

We live a new literary world of 140 character Twitter, personal Facebook dispatches and USA Today snappy prose. The reading audiences of the New York Times who enjoyed reading ‘literature’ has rapidly declined with their subscribers. Or to paraphrase Elmore Leonard, “Literary fiction is when they leave in the boring parts that everybody skips.”

Or to put it another way:

Literary fiction is the fiction of ideas. Its primary purpose is to evoke thought. The writer’s goal is self-expression. Any consideration of the reader—if one exists at all—is purely secondary.

Popular fiction is the fiction of emotion. Its primary purpose is to evoke feelings. The writer’s goal is to entertain the reader. Any consideration of self-expression—if one exists at all—is purely secondary.

One can still hope to write the Great American Novel but if you want to make writing your career – you have to make money. Many experts on writing agree that if revenue is what you seek, then you must write for markets – not for prosperity. Pursue a writing career not so much for fame but for fortune.

I suggest writing stories that are screen-to-print.

So how is that done? What RULES apply?

To do that we need to talk Hemingway.

After he finished “The Old Man and the Sea,” Hemingway wrote his brother, Leichester, telling him that he did not think there was single wasted word in the book. He may be right. The story is a lean, powerful tale. So lean that it may well be the only book ever written to have very nearly every scene transposed into the film version.

So here is rule NUMBER ONE – Think movie scenes and not chapters. Write the story in such a way as how it would look on the big screen. What I am saying is that we can all learn something from Hemingway.

He had some tips for writing well. Use short sentences, use short first paragraphs, (I would add all your paragraphs should be short, sweet and to the point), use vigorous language, say what something is rather than what it isn’t. He learned this style when working as a newspaper reporter.

If you’ve spent any time on the writing discussion boards, you’ll see that the majority of comments about writing style seem to fall into two groups. Those that believe the flowery prose of the literati is real writing and those that feel authors should write to be marketable and choose to eschew obfuscation. Now there are those who believe that paragraphs and even pages of narrative are necessary for successful story telling.

I don’t.

Which brings us to the next set of rules writing Screen-to-Print.

Rule NUMBER TWO. Show. Don’t Tell. Telling is abstract, passive and less involving of the reader. It slows down your pacing, takes away your action and pulls your reader out of your story.

Showing, however, is active and concrete – creating mental images that brings your story and your characters — to life. When you hear about writing that is vivid, evocative and strong, chances are there’s plenty of showing in it. Showing is interactive and encourages the reader to participate in the reading experience by drawing her own conclusions.

Dan Brown’s ‘The Symbol’ suffers from the fate of telling not showing. One critic said he could have cut out 20% of the narrative or chapters and it wouldn’t hurt the story.

So, why is’ showing’ so important to Screen-to-Print?

90% of a screenplay is ‘showing’ – that is, dialogue. There is very little narrative in a screenplay. Very little telling. Except for a few short paragraphs before certain scenes to paint the environment and the mood of the characters, the vast majority of a screenplay is dialogue. The dialogue tells the story.

You have to tell the story through dialogue.

Rule NUMBER THREE. Start your scene in the MIDDLE of the action or start with a dialogue as frequently as you can. A novel should start off by drawing the reader into it right away and give them a hint of mystery of what is to come. I use the device of Prologue in my novels to do this. This breaks another cardinal rule. Editors and publishers claim they don’t like Prologues. I think they can be used to grab the reader’s attention before the actual story starts.

‘Show-Don’t Tell’ types of stories are looked down upon by the literati but I believe that today’s reader – the USA Today and Twitter generation – is not looking for tombs of literature but a quick and entertaining read. Even Michael Crichton honed this down in his later novels. His books were written is such a way that they could easily be turned into screenplays.

There are times where several paragraphs of narrative are necessary to get the story out but always ask yourself first, “Can I SHOW this information instead of TELLING it – and WHEN can I do it?”

Rule NUMBER FOUR. Try to create friction, tension or conflict in every scene – good movies do that. One of the most important elements is the use of conflict and tension.

To quote Tina Morgan:

“Inserting conflict into your novel is not quite as simple as inserting a fist-fight into the storyline. Conflict in fiction can be as diverse and as individual as you are. It can also be used effectively to heightened tension and increase suspense.”

Is your character in enough danger from one chapter to the next? Danger can take many different forms. The easiest and most obvious is the physical danger. Don’t forget to use emotional danger. You as the writer have a moral responsibility to torture these characters as much as you can. Pile on the emotional danger along with the physical.

Analyze a movie – any movie. The best ones that hold your attention are those that know how to put conflict and tension into EVERY scene – even those used for exposition. You know — those boring scenes necessary to get information out.

Don’t leave a finished chapter – or what I call scenes – without re-reading it looking for the inclusion of conflict or tension.

Rule NUMBER FIVE. Write conversationally and kill the semi-colon. Write like you speak – ‘style’ be damned! Or in the words of Dorothy Parker:

“If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style. The first greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy.”

Rule NUMBER SIX. Plot of course drives the story. But what drives the plot? Characters do. In general, you come up with a story idea. Then outline the major plot points that unfold your story idea. This is called a wireframe of your story.

Character behavior drives plot, which drives character behavior. So your next step is to hang the character experiences and behavior on the wire frame of the plot aiming for the sequencing of their experiences to match up with the overall scenes of the plot. If you’re able to do this, then you have a story. All you need to do is fill in the details of each scene.

Rule NUMBER SEVEN. The reversal or the All-Is-Lost-Moment.

Watch movies as they moves along. There is a point where the story is working fine for the hero or heroine – then BAM!! Everything goes to hell for the main character! Two-thirds through the movie there’s this reversal. You can see reversals in romantic comedies too. In fact they are almost always there.

Everything seems to going the hero’s way when all of a sudden, a sub plot appears that threatens to send the hero and his objective into the crap can.

Another example of this is the All-Is-Lost-Moment where it looks like everything is lost. Then the hero resurrects himself. This challenge if faced and the movie then hurtle to its climax. This is important in a novel, too. This challenge if faced and the movie then hurtle to its climax.

Rule NUMBER EIGHT. The Dismissal. Have you ever read a story, following a character through the pages then – they disappear! The reader asks,” What happened to that guy or girl?” Except for the characters that are used one time in a story, your other characters need to be dismissed – that is – have their activities come to a satisfying end. You can’t leave them hanging out there. You need to end their lives or finish their relationships. If you thought out each of you continuing character’s role in moving the plot forward, you will ensure that you have a logical plot structure.

So there you go. Follow these EIGHT rules of screen-to-print and you will have a very readable and enjoyable story where the reader will feel his or her investment in time and money were worth it.

And if you’re up for it – you have a ready made screenplay from your book.

This post is contributed as a Guest post By Author Frank Fiore

Named

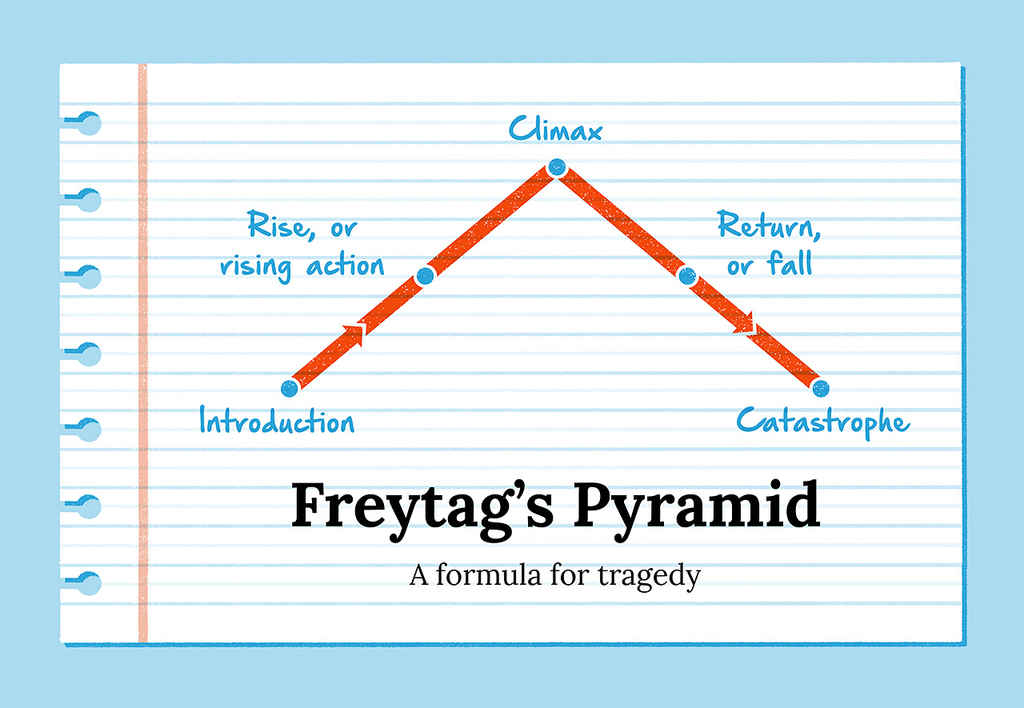

after a 19th-century German novelist and playwright, Freytag’s Pyramid

is a five-point dramatic structure that’s based on the classical Greek

tragedies of Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripedes.

Named

after a 19th-century German novelist and playwright, Freytag’s Pyramid

is a five-point dramatic structure that’s based on the classical Greek

tragedies of Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripedes. Inspired

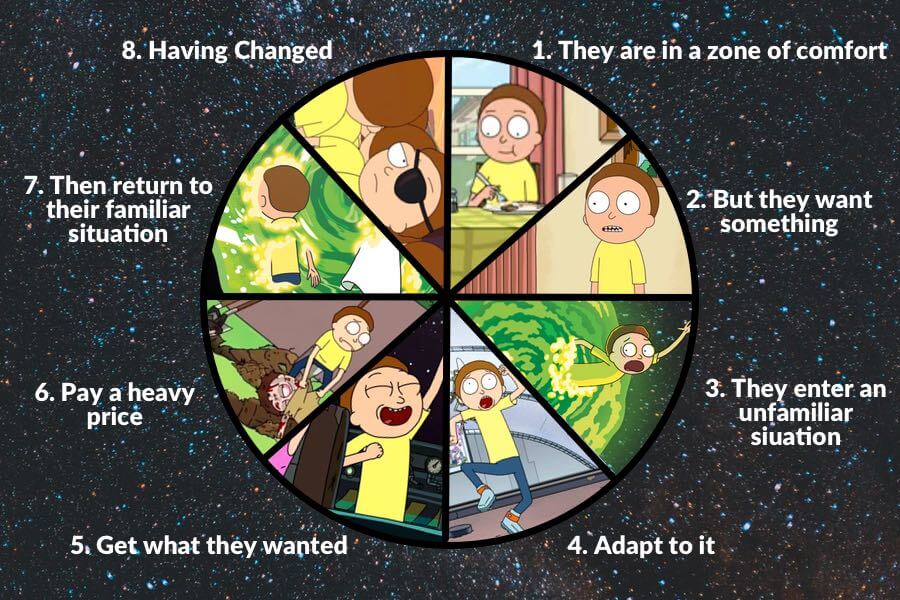

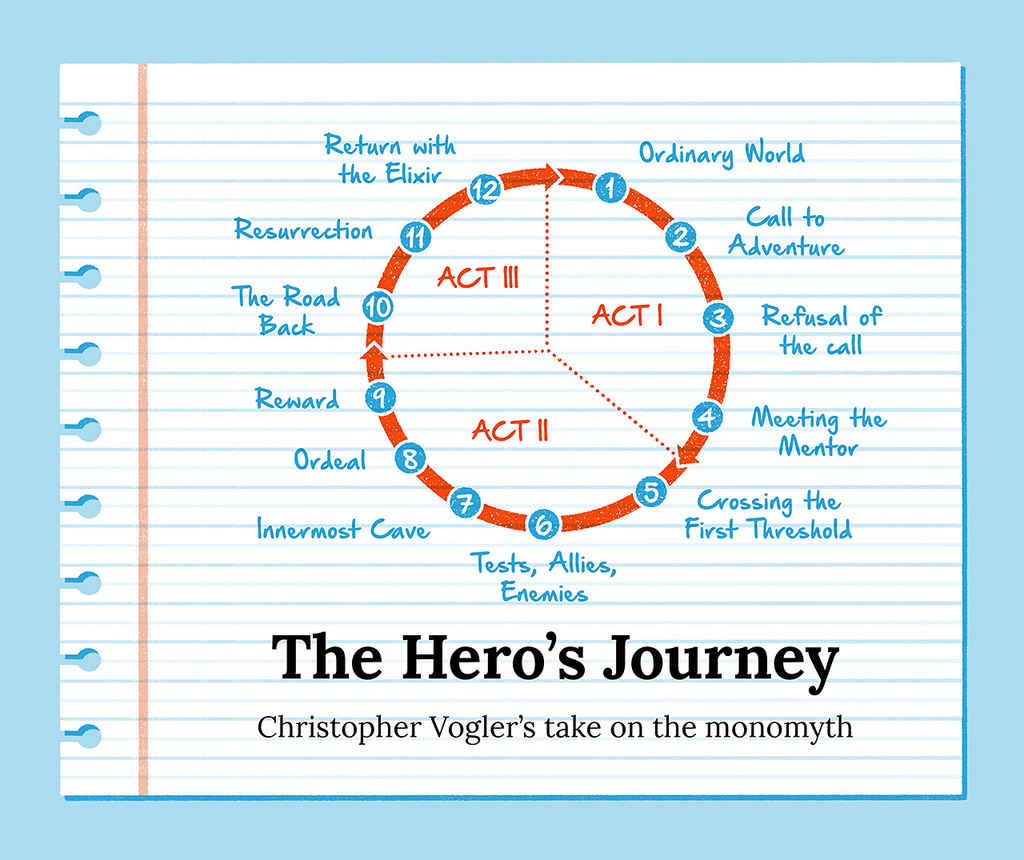

by Joseph Campbell’s concept of the monomyth — a storytelling pattern

that recurs in mythology all over the world — The Hero’s Journey is

today’s best-known story structure. Some attribute its popularity to

George Lucas, whose Star Wars was heavily influenced by Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces.

Inspired

by Joseph Campbell’s concept of the monomyth — a storytelling pattern

that recurs in mythology all over the world — The Hero’s Journey is

today’s best-known story structure. Some attribute its popularity to

George Lucas, whose Star Wars was heavily influenced by Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces.

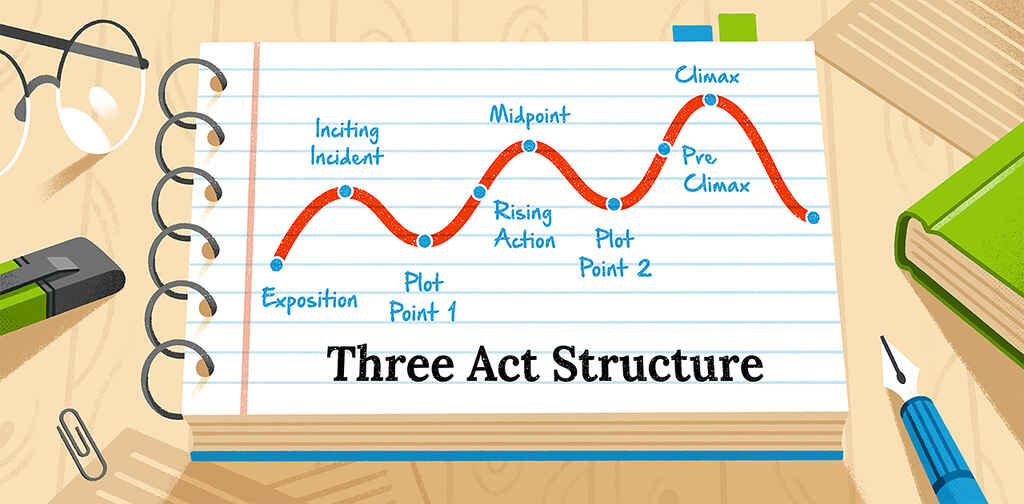

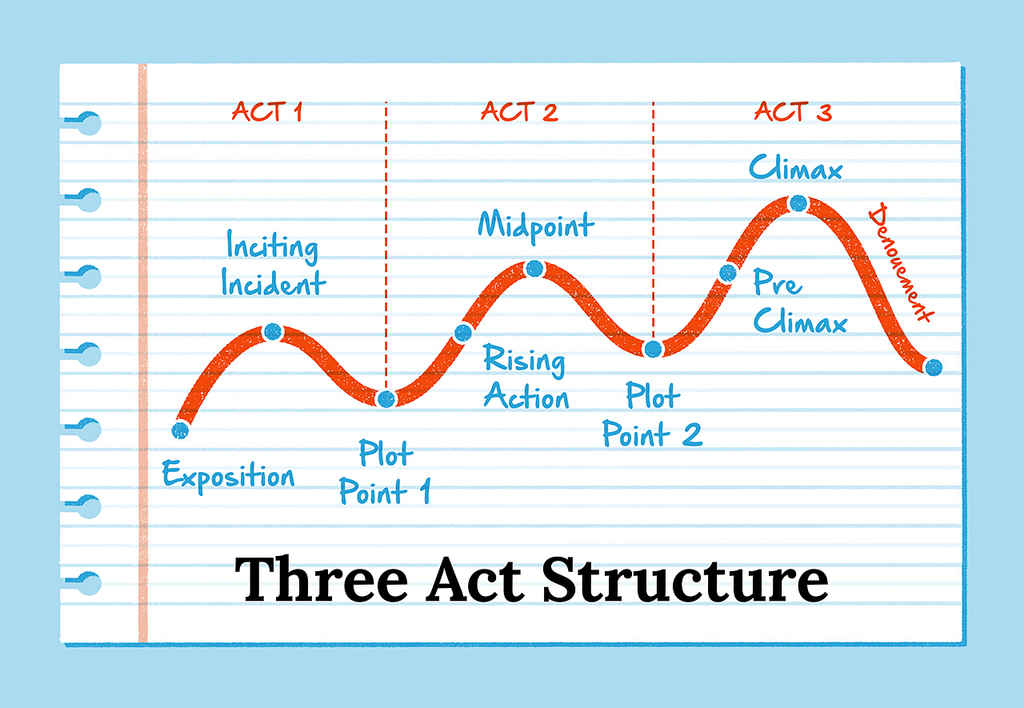

Following

the old adage that “every story has a beginning, middle, and end,” this

popular structure splits a story’s components into three distinct acts:

Setup, Confrontation, and Resolution. In many ways, the three-act

structure reworks The Hero’s Journey, with slightly less exciting

labels.

Following

the old adage that “every story has a beginning, middle, and end,” this

popular structure splits a story’s components into three distinct acts:

Setup, Confrontation, and Resolution. In many ways, the three-act

structure reworks The Hero’s Journey, with slightly less exciting

labels.